How Your Brain Shapes The Story of You

Introduction to how our brains perceive who we are, understanding how you (and by extension others around you) shape your personality and emotions.

I am fond of books by respected neuroscientists and psychologists, especially when they are crafted in a simple way so that even a non-scientist person like myself would understand.

This article, and the subsequent ones in the upcoming weeks exploring the brain and emotions, will be based on two books: “The Brain: The Story of You” by David Eagleman and "How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain" by Lisa Feldman Barrett.

Our thoughts, dreams, memories, and experiences all arise from this strange neural material. Who we are is found within its intricate firing patterns of electrochemical pulses. When that activity stops, so do you. When that activity changes character, due to injury or drugs, you change character in lockstep. — Eagleman, David. The Brain: The Story of You (p. 5)

The brain, that three-pound organ lavishly colored with your agonies and ecstasies, is the emotions maker, shaping who you are.

Let’s dive into our brains and how they shape us…

Our brains are born flexible, not hardwired

The detailed wiring diagram of the human brain is not preprogrammed; instead, genes give very general directions for the blueprints of neural networks, and world experience fine-tunes the rest of the wiring, allowing it to adapt to the local details.

Eagleman, David. The Brain: The Story of You (p. 8).

Unlike many creatures on the planet, human-born babies take years to fully mature. We are born incapable of walking, talking, or feeding ourselves, requiring years to become self-reliant and develop coherent thoughts.

In contrast, if you observe the animal kingdom, you'll notice that nearly all mammals are born with inherent abilities like walking, jumping, and swimming. The skills they need in adulthood are hardwired into their brains and ready for use within a few hours of birth.

At first glance, this might seem advantageous. However, upon deeper reflection, it becomes apparent that if human brains were hardwired, our capacity to adapt would be severely limited.

Eagleman provides an example: if a rhino were placed in the middle of New York City, it would struggle to adapt and likely perish without care. Similarly, if a giraffe found itself in the Arctic mountains, it would face significant challenges and likely succumb.

Humans, in contrast, possess a remarkable ability to adapt to diverse situations and environments. We can thrive in harsh conditions and find solace amidst conflicts. A pertinent example is the current situation in the world where the people of Gaza endure the hardships of war, hunger, thirst, and destruction yet hold onto their faith and resilience.

The human brain’s ability to shape itself to the world into which it’s born has allowed our species to take over every ecosystem on the planet and begin our move into the solar system. — Eagleman, David. The Brain: The Story of You

Emotions

In her book, Barrett described the two theories of how emotions are made:

The classical theory:

Suggests “universal emotions,“ which are: sadness, fear, anger, and happiness.

The same way almost all film productions view it for us: The Sesame Street, Inside Out … etc.

This theory suggests that any human being that ever existed or will exist will be able to extinguish those four different types of emotions, and will express them in the same way.

Barret suggests that there are hundreds of research in the past century that can find a lot of gaps and incompleteness in this theory.

The emotion construction theory:

This is the challenging theory that other groups of scientists (including herself) are suggesting.

This theory suggests that emotions are not hardwired.

Our emotions are constructed based on our upbringing, environment (i.e. where we come from), cultures, and so many other factors.

Emotions are not triggered; your brain creates them.

She admits that this might not seem intuitive at the start, but the more you dive into this theory the more it will make more sense than the classical view (I will dedicate another article on this theory specifically.)

Our Upbringing Shape Us

Eagleman, mentions that it takes humans 0-21 years to fully shape their personalities. This means that our adulthood experiences, habits, and upbringing, shape our personalities significantly, and of course our childhood.

Childhood

Our brain learns and perceives anything by connecting neurons.

A synapse is like a path between neurons. If you don’t use these paths, they will eventually fade and get removed from your brain.

This means, that who we are is not only defined by what’s grown in our brains, but also by what hasn’t.

Both Eagleman and Barret suggest that childhood and the way we were raised shape:

Who we are

What we believe in, and as importantly what we don’t believe in

How we express our emotions

How we feel in different situations

For example, someone who has lost a loved one may sympathize deeply with anyone who lost a loved one to the extent that they may feel sad or even cry. As opposed to someone else who hasn’t dealt with the loss of a loved one before, they’ll probably sympathize with the news but won’t feel deeply sad or show any sadness expression at all.

A case study

Without an environment with emotional care and cognitive stimulation, the human brain cannot develop normally.

Eagleman, David. The Brain: The Story of You (p. 13).

Eagleman discusses the example of Romanian orphans to illustrate the critical role of early life experiences in shaping the brain and, consequently, one's cognitive and emotional development.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Romania experienced a political regime change that led to widespread poverty and a lack of resources for child care. As a result, many children were placed in overcrowded and understaffed orphanages, where they experienced severe neglect (they saw only one nurse in their lives, and they were never touched, hugged, or kissed).

Eagleman uses this example to

Highlight the impact of early adversity on brain development.

The lack of individualized care, emotional support, and cognitive stimulation in these orphanages had profound consequences on the orphans' neural pathways.

Many of them faced cognitive, emotional, and social challenges as they grew older.

This example serves as a powerful illustration of the brain's plasticity — its ability to adapt and change in response to experiences.

It underscores the importance of a nurturing and enriching environment in early childhood for optimal brain development and the formation of a healthy sense of self.

Adolescence

Teens are not only emotionally hypersensitive but also less able to control their emotions than adults.

Eagleman, David. The Brain: The Story of You (p. 17).

During our teenage years, we undergo hormonal shifts and surprises, with our brains exhibiting a heightened inclination for risk-taking compared to adulthood.

Simultaneously, there is a growing anxiety to be accepted by our "tribes," as we yearn to find a sense of belonging.

The friendships we cultivate during adolescence play a significant role in shaping our future selves. The synaptic connections (neuron pathways) formed during these years become deeply ingrained in our brains, making it more challenging to alter the characteristics or habits acquired during this crucial developmental phase.

This underscores the importance for parents or families raising teenagers to create a supportive and positive environment. Choosing such an environment becomes pivotal in influencing the kind of responsible and healthy adults they hope their teenage children will grow up to become.

Who we are as a teenager is not simply the result of a choice or an attitude; it is the product of a period of intense and inevitable neural change.

Eagleman, David. The Brain: The Story of You (pp. 17-18)

Adulthood and Plasticity

After all the tremendous shifts in our identities in childhood and adulthood, our brains now appear to be fully matured. You may think that what we learned is immovable. And, as adults, we are fixed and can’t or won’t change.

This is utterly and completely not true.

We can continually (even in old age) change who we are, learn new skills, and build new synapses and neural connections in our brains. This process is known as Plasticity.

Plasticity/Neuroplasticity is a key factor in various aspects of cognition, memory, and recovery from brain injuries. It underlies the brain's capacity to adapt to new information, acquire new skills, and recover from damage. The understanding of neuroplasticity has significant implications for fields such as education, rehabilitation, and neuroscience research.

There are two primary types of neuroplasticity:

Structural Plasticity: This involves physical changes in the brain's structure, such as the growth of new dendrites (branch-like extensions of neurons) and the formation of new synapses. Structural plasticity is crucial for learning and memory.

Functional Plasticity: This refers to the brain's ability to move functions from damaged areas to undamaged areas. For example, if one part of the brain is injured, another part may take over certain functions to compensate for the damage.

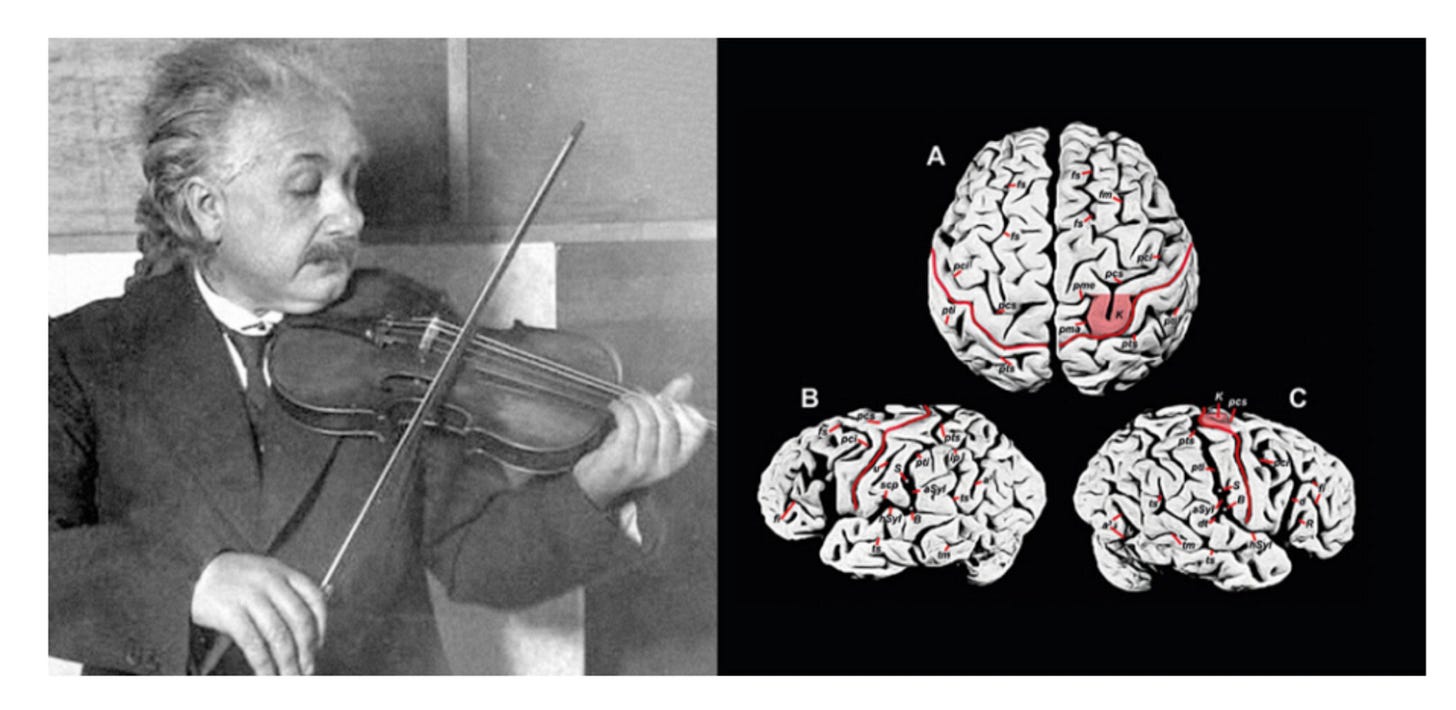

To translate this into a solid example: when Einstein's brain was analyzed in research to find the secrets behind his genius, although there was no physical evidence in the brain to distinguish his brain from others, scientists discovered another interesting thing.

Einstein was less known for his ability to play the violin, they found that the brain area that is associated with his left finger had grown giantly, forming a deep and enormous number of connections.

This formation in the brain is common among experienced violin players.

Your family of origin, your culture, your friends, your work, every movie you’ve watched, every conversation you’ve had – these have all left their footprints in your nervous system. These indelible, microscopic impressions accumulate to make you who you are and to constrain who you can become.

Eagleman, David. The Brain: The Story of You (p. 20).

Summary

The brain's wiring is not preprogrammed; genes offer general directions, and life experiences fine-tune neural networks, highlighting the brain's flexibility.

Humans are highly adaptable, compared to the animal kingdom, because our brains have the ability to connect new neurons by gaining new skills and learning.

Emotion theories include the classical view of universal emotions and the emotion construction theory, suggesting emotions are not hardwired but shaped by upbringing and environment.

Childhood and adolescence experiences significantly shape personality, beliefs, and emotional expressions, with synapses formed during this time influencing adulthood characteristics.

Neuroplasticity enables the brain to change and adapt even in old age, challenging the notion of fixed identities in adulthood.

Adults can change, but this will need guidance, consistent effort, and embracing environments

Be careful of who you are surrounded with and what you consume: The cumulative impact of family, culture, friends, work, movies, and conversations shapes an individual's nervous system and identity.

In the following weeks, we’ll discuss:

Our identity is seen by our memory, what our memory is, and most importantly what it is not.

Emotions: how they are constructed

And, more topics from the emotions and the brain books.

Let me know in the comments if you would like other topics discussed! I'd be happy to talk about what interests you.

Thank you for reading until this point! If you liked what you read and want to help other people find it, click the ❤️ button below.

Thank you for this article. It reminds me why each person is so unique since we are all influenced by our experiences and why we think differently about various topics. Since I am an American and have had various influences on my thinking and way of being, I can understand why my Lebanese husband thinks very differently than I do about many things. Mostly, we agree to disagree about things that we see differently. It’s not about who is right or wrong.

Thank-you!